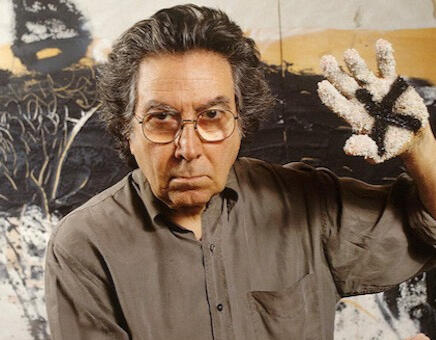

Antoni Tàpies painter, sculptor and art theorist.

At just 18 years old, Tàpies suffered a serious lung disease that kept him convalescing between 1942 and 1943, a period in which he devoted himself to copying drawings and paintings by artists such as Van Gogh and Picasso. The self-portraits made by Tàpies at the beginning of his career avoid academic drawing and show the influence of references such as Matisse or the aforementioned Picasso. The self-portrait offers artists the possibility of exercising the study of anatomy with the closest model. Tàpies's early work also announces the introspective nature that characterized his production from then on. In this first stage, in which a notable influence of artists such as Joan Miró, Max Ernst or Paul Klee can be perceived, some of the themes and techniques that underpin his plastic language were outlined, such as self-referential symbols and calligraphy, perforations and incisions, landscapes or the ambiguity of the body and sexuality.In 1948, together with figures such as the poet Joan Brossa, the theorist Arnau Puig and other painters such as Joan Ponç, he founded the Catalan avant- garde group Dau al Set - created around the magazine of the same name - which played a relevant role in the artistic renewal of post-war Spain.For a little over three years, Tàpies' painting underwent an iconographic turn accentuated by fantastic and lyrical qualities, reminiscent of magic. The use of geometric elements and the study of colour soon aroused in the artist an interest in matter, which became visible in enigmatic canvases with suggestive and dynamic spaces.

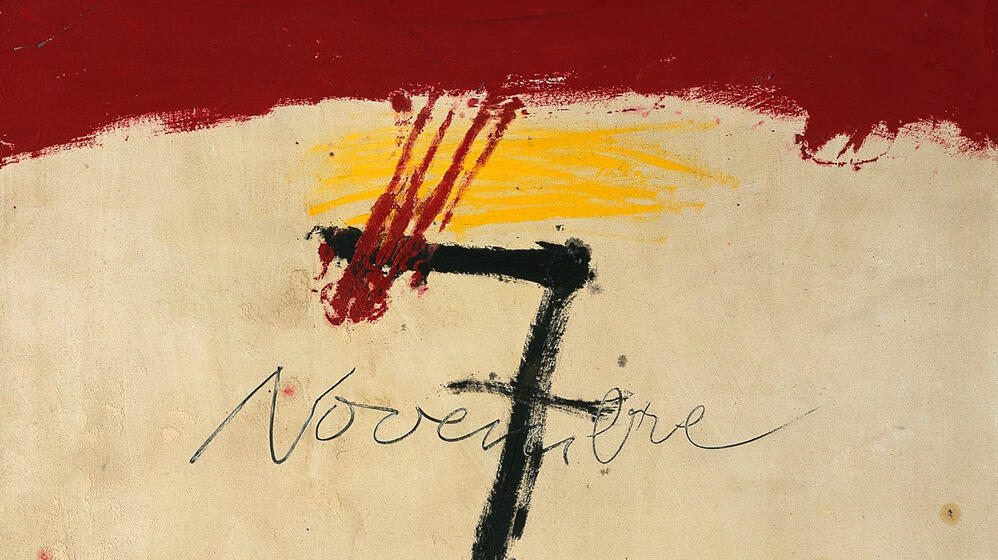

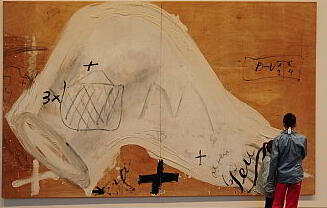

With a scholarship from the French Institute in Barcelona, between 1950 and 1951 Tàpies lived in Paris, where he met Picasso and came into contact with the international avant-garde movements.From 1953 onwards, there was an important turning point in his career, moving towards a material expression that would transcend his apparent link with abstraction. This turn allowed him to subvert the traditional conception of the pictorial surface, incorporating dense textures similar to those on a wall or fence, to which he applied incisions, marks, footprints, scribbles, perforations, etc. The imprint of the material trace caused by the passage of time, visible in the reality of all types of walls, gives these paintings an almost geological, “wall” appearance, which has degradation and deterioration as a common denominator. The critical reception of these works produced in the 1950s soon placed him in a prominent place in the national and international avant-garde.A series of solo and group exhibitions, as well as a multitude of awards, confirmed the widespread recognition of his work, which was shown in events first-rate institutions such as the Carnegie International, the Venice Biennale, the São Paulo Biennale, the Kassel documenta, or institutions such as the MoMA and the Guggenheim in New York.Throughout the 1960s, Tàpies' production of material paintings took a turn with the incorporation of lements of external reality that responded to his concerns about broadening the notion of realism. The action of adding recognizable objects, often used and banal, entailed an approximation to the real and concrete that denoted a step beyond in terms of representation. It is at this moment that the question of the human body became increasingly important in his work, becoming evident in the explicit representation of certain parts of it. Tàpies explored visual ambiguity by forming or deforming what was represented,without the matter ceasing to acquire the form of that to which it is associated, as in Matèria en forma de peu [Matter in the Shape of a Foot, 1965]. The paintings do not “re-present” anything, because there is no separation between subject and object, but rather what is important in them is their becoming.Tàpies' political commitment to Francoism became increasingly explicit. For example, in 1966 the artist was arrested after taking part in a clandestine meeting of students and intellectuals at the Capuchin Convent in Sarrià (Barcelona), which had been convened to discuss the creation of the first democratic university union, and in 1970 he attended a clandestine assembly at the Montserrat monastery to protest against the so-called Burgos Trial, through which a military court judged opponents of General Franco's regime. His political involvement against the dictatorship was personal and artistic. According to the artist himself: "the social and political situation in my country has always had an impact on my work.I think that has to do with the fact that the conception of art for art's sake doesn't appeal to me. It is valid. I have always maintained a utilitarian attitude towards art.” This is evident, as if they were history paintings, in works such as A la memòria de Salvador Puig Antich [In memory of Salvador Puig Antich, 1974], a tribute to the young anarchist executed by the regime.In the early 1980s, his painting showed slight formal and conceptual changes that pointed to a refinement of material weight, without such a distinctive element as the “wall” ceasing to be present. The formats gained size and the strokes extended over larger surfaces, making the scale contribute to the more sedate character of the works, with hardly any variations in the artist’s recognizable repertoire. It was at this stage that the use of varnish became prominent. This golden-hued material summons the unpredictable and chance, playing with transparency, disorder, stains and formlessness.He fuses almost figurative forms that later dissolve into abstractions of disturbing ambiguity. The use of this material was accompanied by a growing interest in oriental culture and art. Works such as Celebració de la mel [Celebration of Honey, 1989] serve as a paradigmatic example of both aspects. In the last two decades of his life, Antoni Tàpies' work became imbued with a certain feeling of melancholy. The artist continued to enjoy great recognition, but his work was dominated by despondency and constant references to death, illness and pain. Faced with the awareness of the proximity of death, Tàpies found ways to live with the certainty of the passage of time, but not to victimize himself or abandon himself. The paintings from these mature years do not lose that uncomfortable indeterminacy between figuration and its dissolution, but rather evoke erasure and oblivion. They are memories and experiences that form part of the memory of his own gestures.